In my essay Where Do The Children Play, I argued against the proponents of secularisation who argue religion is on an inevitable linear decline in the West. I still stand by most of what I wrote in that article — I do think there will be significant growth in more traditional religious sects relative to the rest of the population. However, on the scale of mass-society, I think the proponents of the secularisation thesis are basically correct, and there are a few important points to make regarding the limited scope of the return to religiosity I discussed in that essay.

Since writing that essay, there are some things I have reconsidered which, if true, seem to place a hard limit on the scope of a return to religiosity. First, the heritability of religion is slightly lower than some oft-cited studies suggest. Secondly, a closer look at religiosity in the US has led me to conclude that its purported exceptionalism is likely overblown. Seeking an explanation for American religiosity is what originally made me sympathetic to the “religious marketplace” argument made by some sociologists of religion, who argue that modernity will lead to a religious revival. Looking at this model more critically, there are a number of problems with the way the supposed evidence for it is presented, and some very noticeable trends in the West seem to fly in the face of the trends this model predicts.

In fact, all signs point to pluralism and individualism being at the root of secularisation, and if that’s the case, the outlook for religion is very grim. Allow me to explain.

The heritability of religion

Firstly, let’s talk about the heritability of religiosity. Opponents of the secularisation thesis on the right have made much of this, but it has to be noted that it is often exaggerated. In The Past is a Future Country, Ed Dutton draws on a 2008 study by Bradshaw and Ellison to argue the genetic heritability of religion is 0.4.1 This study measured the genetic and environmental effect on a number of religious measures, and while markers of “conservative religiosity” like biblical literalism were as high as 0.44 genetic, involvement with organised religion and church attendance were a bit lower, at 0.32. Religious salience, or religion being an important part of someone’s life, was just 0.27 genetic.2

This study was included in a meta-analysis of studies on the genetic influence on religion produced in 2020.3 This study breaks down the categories of religiosity into “internalised” and “externalised” religiosity. Externalised religiosity is someone’s tendency to attend religious services, take part in religious study groups etc., while internalised religiousness reflects the extent of religious beliefs and the importance of religion in someone’s life. Externalised religiousness is more genetic, estimated at 0.39, but this is a measure of how people that are already religious practice their religion. The more relevant category if we are to forecast how much religiosity will be passed on genetically is internalised religiosity, and this is found to be 28% genetic.

Religion has a lot more to do with genetics than most would ever consider, but it’s not large enough to think the religious segments of the population will overtake the non-religious any time soon, even with greater birthrates, and especially if secularisation is having a greater effect than ever on the 72% of the equation that is environmental.

The scale of secularisation

The secularisation thesis argues that religious authority and influence declines in all aspects of social life when exposed to the forces of modernity. This should be applied specifically to the West, since not all societies have undergone the same process of rationalisation that has played out in the West since at least the Enlightenment. For various reasons, we shouldn’t make the mistake of extrapolating the endurance of religion in the Middle-East or Africa to the West.

Looking at global numbers of religiously affiliated people, it’s easy to see how someone could dismiss talk of secularisation: not a single country in Africa, North America, or the Middle East have a majority secular population. Uruguay is the sole country in the Americas where a majority of the population are religiously unaffiliated. But what secularisation really looks like is indifference. In many European countries, a majority still nominally identify as Christian, but church attendance is extremely low and declining, and Christian moral teaching has less influence than ever on society. Politics in European countries where a majority still identify as Christian is mostly free of Christian influence, with the Church’s moral teachings absent from policy debates or election campaigns.

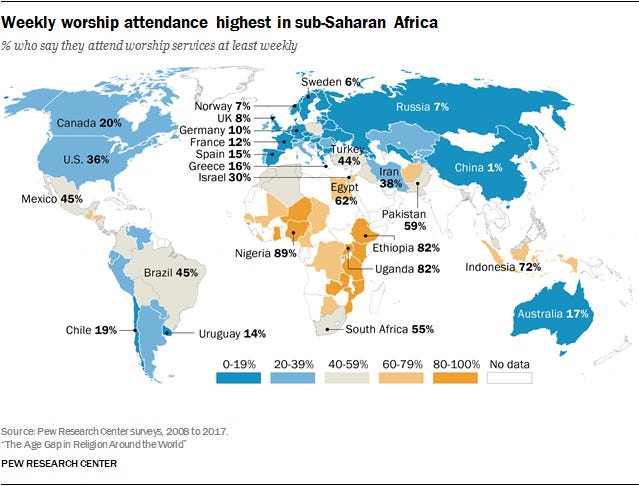

Fewer than 20% of people attend a weekly church service in countries like Germany, France and Spain, and that number is under 10% in Northern European countries like Denmark, Norway and Sweden. In conservative Russia, the number is only 7%. Only 6% of people in the UK engage in daily prayer, and only 9% of Germans. To make matters worse, in Europe this is heavily skewed to the older segment of the population who grew up in a more religious world, and will decline more as that generation dies.

The not-so-exceptional exceptions

Opponents of the secularisation thesis often point to countries in Eastern Europe that have seen a revival of religiosity in recent decades. But most of these countries are former republics of the Soviet Union, where religion was aggressively repressed by the state. As such, the low levels of religion reported before the 1990s were not the result of modernisation, but the numbers being artificially depressed by the actions of the state.

What has happened since is just a reflection of the existing religiosity of the people in those states, but this does not mean they will be any more immune to the effects of modernisation with time. Indeed, in many of these countries we are already seeing a rapid decline in religiousness. In a decade from 2011 to 2021, the percent of Polish people identifying as Catholic fell from 88% to 71%. The fraction that attend weekly mass fell from 58% before 2005 to 39% in 2024

The US may not be so exceptional either. Although Americans are more religious than their European counterparts by all metrics, Christianity is still on the decline, and it is more marginalised as a political force than ever. To the surprise of many sociologists, the United States has remained stubbornly religious, with 68% still identifying as Christian. Yet when polled, only 38% of Americans say they consider abortion morally wrong, something obviously at odds with any Christian faith. Only 29% now say they oppose gay marriage.

One thing that skewed data on American religiosity is that Americans simply lie more when polled about their church attendance. In the early 1990s, a team of sociologists set out to discover why reported church attendance remained the same, despite the fact that those surveyed also consistently reported that they attended “less frequently”. Studying the real attendance of congregations in Ashtabula County, Ohio, they concluded the observance claimed by respondents was 83% higher than their best estimates of actual attendance. Further research conducted across the United States concluded church attendance was probably about half of what was being self-reported.4 Responding to this work, a consensus emerged of about 20% of Americans actually attending a church service weekly, making the US seem much less of an anomaly compared to Europe.

But now, the number is far lower still. While 21% to 30% still self-report attending church weekly, this year the Washington Post put together a team of data analysts to study the U.S. Religious Census, who concluded that the rate of weekly attendance was a dismal 5%. Devin Pope, an economist at the University of Chicago, used cell phone data to track where people actually were at church time, and also concluded the number was likely 5%, though perhaps as high as 6% if accounting for groups like Orthodox Jews and Amish who would not have cell phones to track.

Aside from the numbers identifying as Christian, the US seems unique from Europe in how strong a role Christianity plays in its politics, especially since the emergence of the “moral majority” in the 1970s. Yet the emergence of a stronger Christian right has led to few legislative achievements, and has failed in its quest to reverse the trend of secularisation in the country. Laws around homosexuality and the secularisation of education continue to favour the liberal social agenda; the American divorce rate climbed to one of the highest in the world; taboos against deviant sexual lifestyles, out of wedlock births and abortion declined; and the country accepted gay marriage. When religious conservatives finally achieved a big victory with the overturning of the Roe v Wade supreme court decision on abortion, voters rejected abortion bans in referendums in red states like Kentucky and Kansas. By now, the public has so roundly rejected abortion restrictions that Donald Trump has felt the need to emphasise a moderate stance on abortion and promise not to legislate a ban.

Modernity vs. Religion

The reasons for secularisation in the West are numerous, and each one could be (and is) the topic of its own book. There are deep roots in the theology of Christianity: monotheism replacing animism and removing a spiritual background to things people took for granted; the consistent and clear demands and moral order of a single God encouraging rationalism; Christian nominalism making naturalism seem like a plausible alternative to God. All these have been put forward as explanations for the West’s eventual embrace of secularism.

These all have their place, but the more immediate causes of secularisation are the revolutionary economic and social changes that have come since the industrial revolution. The main effect of these changes which has been particularly devastating to religion, is individualism. Religion is now elective in a way it wasn’t in other epochs. Society has become complex and stratified in a way that has disrupted older forms of community where religion and the authority of elders was more taken for granted. Religion thrives in small, close knit communities. It disintegrates among the masses. As Steve Bruce writes:

As the society rather than the community becomes the locus of the individual’s life, so religion is denuded. The parish church of the Middle Ages christened, married, and buried. Its calendar of services mapped onto the seasons. It celebrated and legitimated local life. In turn it drew strength from being frequently reaffirmed by the local people. In 1898 almost everyone in my village celebrated the harvest by bringing tokens of their produce to the church. In 1998 a very small number of people in my village, only one of them a farmer, celebrated by bringing to the church vegetables and tinned goods (many of foreign provenance) bought in a supermarket that was itself part of a multinational combine. Instead of celebrating the harvest, the service thanked God for all his creation.4

The individualism and complexification of mass-society also exposes people to the astonishing pluralism of religious belief. By far, the strongest factor propping up religion historically is that the vast majority of its practitioners just took it for granted. This is not possible for most when they become aware that their religion is one of many, that there are various similar and competing branches of their own religion, that some profess no religion at all, that some have their own form of spirituality or selective religious belief, etc.

Most people who were raised in a religious household probably remember a time at which they realised there were competing views about God and the universe, and what their parents had taught them suddenly lost its taken-for-grantedness. While many sustain the faith of their birth through this challenge, many do not. This was not a trial faced by most of our ancestors, who spent their lives in communities of like-minded kin, worshipping the same God and attending the same church. This exposure to pluralism is exacerbated by the advance in communications technology.

This is more of a problem for Christianity than other religions. While religions like Buddhism, Taoism, and Hinduism are compatible with a perennialist or religious pluralist view (many pathways to one summit), Christianity makes a claim to be the one correct path to God. For many, it is difficult to hold the idea that most of the world faces either eternal damnation or a denial of God’s infinite love by accident of birth, because of faithfulness to their own father’s religion, or because of mistakenly reasoning their way to the wrong belief system. While a Taoist can learn about the practices of a Christian or a Muslim and find reflections of the same truth expressed in their own particular religion, a Christian must face up to the enormous pluralism of faiths and contend that they are all wrong. They must affirm that they alone are correct and have the one right way to God.

There is also the simple fact that modernisation has made most of us wealthier, healthier, and more comfortable than our recent ancestors could have imagined. Religious belief is increased by mortality salience, and in a world where there are few material consolations for the average person, and death is far more present and visible, religion is a beautiful consolation. Christianity now is not just competing against Islam, Buddhism and new age spirituality, it is competing against all the enjoyments, distractions, sports, self-help philosophies and adventures that modern technological society can offer. A religious philosopher can argue that these are all just so many distractions to fill the God-shaped hole in the hearts of moderns, but how many will listen when that too has to compete with the rest of the attention economy?

The free market failure

As mentioned, I previously drew on the “Supply-side,” or “Rational-Choice” model of religion promoted by Rodney Stark, one of the greatest sociologists of religion. This was sparked by a search to explain the resilience of religion in the United States, but, as I’ve demonstrated, that has been much exaggerated. Still, Stark and other scholars produced a very large body of work to verify this theory, and many of their studies seemed convincing. The theory also has some intuitive plausibility: won’t clergy work harder to put butts in seats in a “free market” where their living depends on it? Stark often cited examples of Catholic parishes in decline, where the local priest or bishop had apparently stopped caring about appealing to the laity due to the comfort of their positions.

But there are serious problems with using a “rational choice” model for something like religion, most of all, that religious expression is one of the areas of life least commanded by reason. Just go back to the example of the negligent priests, the rational choice model says the clergyman with a monopoly facing no competition will lose motivation to attract followers. But obviously, a clergyman has a strong sense of a motivation other than self-interest, the same thing that made him give up his self-interest of finding a wife, having a family, pursuing a more lucrative career, etc. There are other careers where we don’t assume this kind of thinking applies: we don’t expect an experienced, tenured professor to give bad lectures to his students because of his job security — we know someone of that prestige carries a certain pride and passion in their vocation.

As for the argument that exercise of rational choice by the laity makes them more likely to return to religion when their options range from a sombre Latin mass to the lively worship of an evangelical church, there is every reason to imagine that this pluralism might have the opposite effect. As I’ve argued, seeing diversity of religious expressions is more likely to make a rational person suspect they are all wrong in their own unique way, than sift through them finding the one they think is right for them.

But what about the data presented for this model? One issue is that supply-siders rest on an implicit assumption that the US is uniformly “diverse”, while actually reporting high religiosity in areas that are locally homogeneous. While religious diversity is high in the US overall, this doesn’t have a lot of bearing on the experience of a Mormon growing up in a homogeneous community in Utah. And the more you remove people from these local pockets of religious homogeneity, the more religion seems to decline.

After decades of debate about the “supply-side” model, two sociologists produced a study taking into account 193 different analyses of religious pluralism, of which only 24 seemed to support the claim of supply-siders. The authors conclude that the:

Absence of any general positive relationship between pluralism and participation does not bode well for the more general idea that market-like religious competition promotes religious vitality.5

Putting the sociology papers aside, supply-siders like Stark have been making these predictions of religious pluralism bolstering religion for decades, but what have we observed? The United Kingdom, with its Protestant tradition, open society, and all the religious diversity its racial diversity has brought in recent years, should be seeing a religious renaissance. Yet encountering Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs hasn’t pushed more people to try out one of the hundreds of Christian sects on offer. Among young people in Britain coming of age in this pluralist environment, just 2% identify with the Church of England. Within Europe, more pluralist, historically Protestant countries in the North continue to be more irreligious than Southern European countries where Catholicism was dominant.

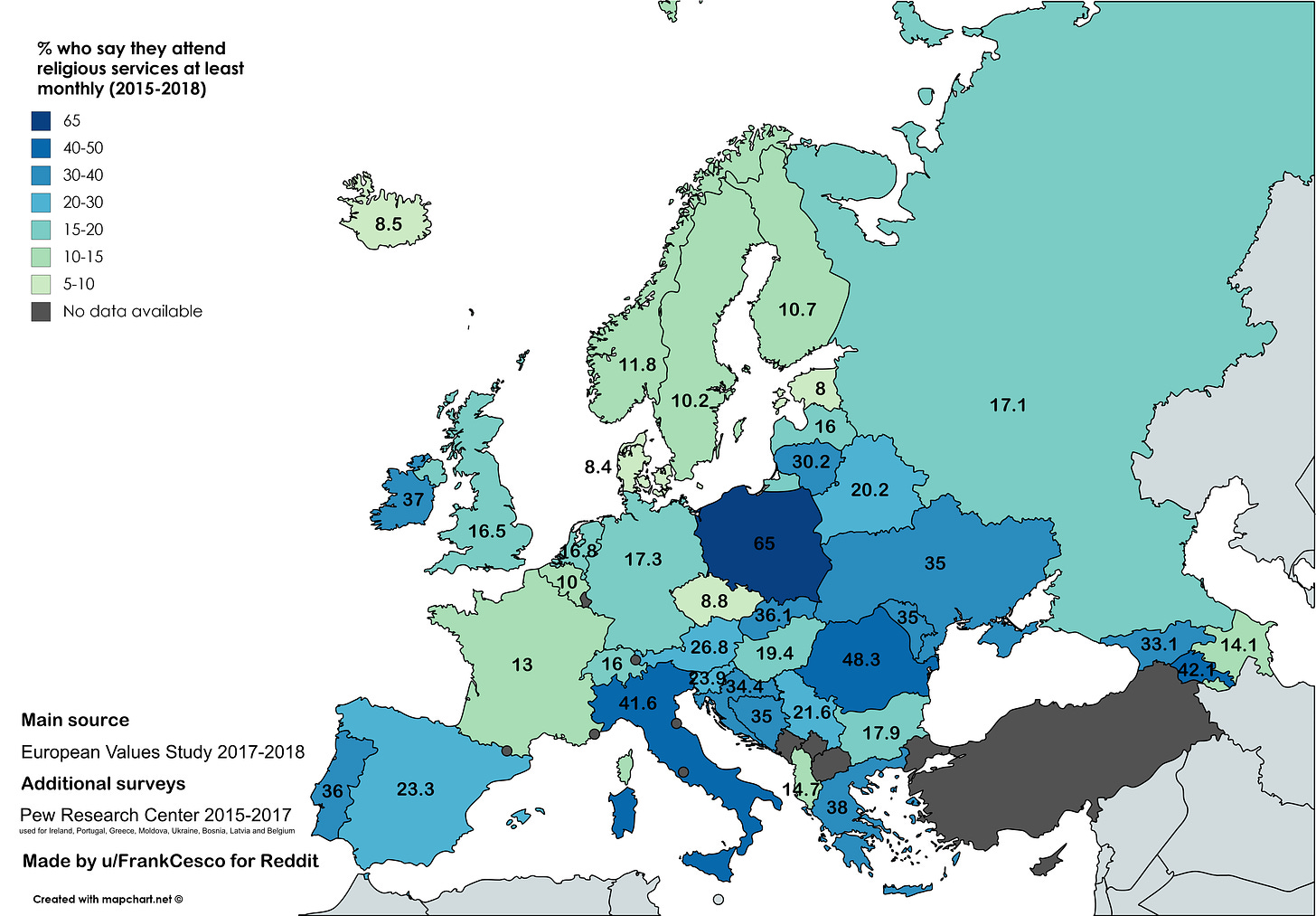

If we zoom in further, and compare the very similar Baltic countries, Lithuania has by far the highest rates of church attendance. The fraction of Lithuanians who attended church monthly was polled at 30.2%, but just 8% in Estonia. In fact, Estonia — which is the most economically developed of the Baltic states — is one of the least religious countries in the world, but its remaining share of Christians is quite pluralist, with just over 16% belonging to the Orthodox church and 7.7% to Lutheranism. Lithuania is the most homogeneous religiously, with three-quarters of the population belonging to the Catholic Church. Just 3.75% of Lithuanians belong to the next largest denomination of the Orthodox Church.

The Pagan non-answer

Many on the radical right affirm the trends identified by theorists of secularisation, but argue that the cause is different. Europeans, they say, are naturally rejecting a foreign religion that was never suited to them. As inevitable as it was that they would throw off this foreign desert religion, it is also inevitable they will return to their natural forms of pagan religion. Will the secularisation theorists and hopeful Christians both be blown away by a renaissance of paganism? I don’t think so.

First of all, there are very few Pagans. So few that this would not warrant discussion if not for the bullish predictions of a pagan future from dissident thinkers who are worth taking seriously. There are 74,000 pagans in the UK, fewer than one in 500. In Ireland, that rate is fewer than one in a thousand. 0.3% of Americans identify with some form of paganism or new age spirituality, but this is obviously a very diverse bunch. There are White nationalist heathens who view their religion as an extension of their politics, feminist wiccan witches celebrating full moons, eclectic classicists celebrating Hellenic paganism, etc.

Even among the already tiny niche of nationalist pagans, there is far more divergence than among all the sects of Christianity. Some worship the Germanic gods, some the Greek. Some think those gods are real and worthy of devotion, some view them as real spiritual archetypes that can influence the world, some are naturalists that view them as metaphors for the forces of nature. Some revere Plato as a sage and the finest exponent of pagan philosophy, others view Plato as a subversive who destroyed the traditional pagan worldview and helped usher Europeans into the decadent axial age. Paganism is already extremely niche, and it’s hard to imagine any one of these niche subsects achieving breakout growth.

For many of its adherents, it’s hard to know if it really qualifies as a religion at all.

Religion isn’t just anything people think is really important or find meaning in — sports, science, transgenderism or climate change are not actually “the new religion”. Remember, secularisation is not so much about fewer people professing a religion, so much as just becoming indifferent to religion as its authority declines. How many pagans are really under the authority of paganism? Most right-wing pagans seem to decide to be a pagan as a logical next-step in their political development. They conclude Europeans need a native, vitalist, moralising spiritual life, and they choose which type of paganism would be the best fit. Only, try as you might to reject reason and empiricism as symptoms of Jewish-Christian modernity, you can’t really just choose to believe in the gods. If your religion is an attempt at spreading a worldview that you think will moralise people to accomplish the political goals you want, then it’s not a religion, but a political project.

This gets to a more fundamental problem with attempting a return to paganism: monotheism completely changed how we think about the world, the divine, and our relation to it. The religious scholar Jan Assman described it as “an umbilical cord was severed that cannot be reconnected”.6 There isn’t a living tradition of paganism that reconnects us to the rites and traditions of the people who first carried it, and what is paganism if not that?

Conclusion

I felt this was a necessary addendum to my other essay on religious trends. However, the main trends I identified there still exist. More conservative people are having more children, while the most left-wing among us are not, and are disappearing fast. States that are ethnically homogeneous, religious and socially conservative will be able to buck the trend of falling birthrates unlike any others. Smaller, more conservative sects like traditional Catholics and Mormons will grow a lot relative to others. But whatever optimism this might inspire among the religious should be tempered by a reminder that this is happening against a background of collapsing religiosity overall.

Not only is society becoming less religious, but religion is losing its political authority. These trends also mean religion will become more fragmented. There will be more thriving sects of homogeneous religious communities, but at the cost of societies where 80% or 90% share one religion with one agreed upon set of morals. Maybe there will be more conservative religious people in the future, but can a smattering of more traditional and fundamentalist Catholics, Mormons, Baptists and Presbyterians form a cohesive political coalition? The failure of the religious right in the 20th Century, in countries where the majority of the population shared a faith, should make us skeptical.

The religiously homogeneous societies of the West in the 20th Century were a product of a world where the community was the central locus of authority and meaning. As people became the individuals of mass-society, religious authority declined. On the level of mass-society, we should expect secularisation to continue and religious dialogue to remain isolated from the public square. But on the fringes of mass-society, strong religious communities will thrive again. Secularism might be here to stay, but there will be new Byzantiums for those who want to grab a lifeboat.

References: