The Irish election results were a little disappointing, but also pretty much what I and most nationalists I spoke to expected. Although it’s disappointing there was no breakthrough, there are signs of things trending in a positive direction. Now that the dust has settled and we have the final results and lots of data on who voted and why, I want to try and draw some lessons. Read my initial response here.

First of all, the problem with starting from the kind of low base Irish nationalism had a few years ago is it’s difficult to temper expectations about the long, slow building phase while also moralising them to get involved. Remember that the Irish right pre-COVID was basically a bunch of livestreamers, assorted Twitter personalities, and a couple of upstart parties with no electoral record. Turning that into a real force in a political system as tribal as Ireland’s was always going to take a lot of work.

Here’s what typically happens in nationalist circles: people see how rapid demographic change is because of mass-immigration and conclude that if we don’t get control of the government in the next decade it’s over. With a strict command of “no blackpilling”, many convince themselves the people are about to wake up, and we allow delusional levels of optimism to spread about what’s possible.

No one wants to be the person spoiling the fun telling people that most of the country still thinks their ideas are abhorrent and a realistic goal might be just increasing the vote share and taking a seat or two. But without tempered expectations, you get a period of deflation after an election where people announce they are emigrating, never voting again, or have had a realisation that cosplaying as a militia unit is actually the way forward.

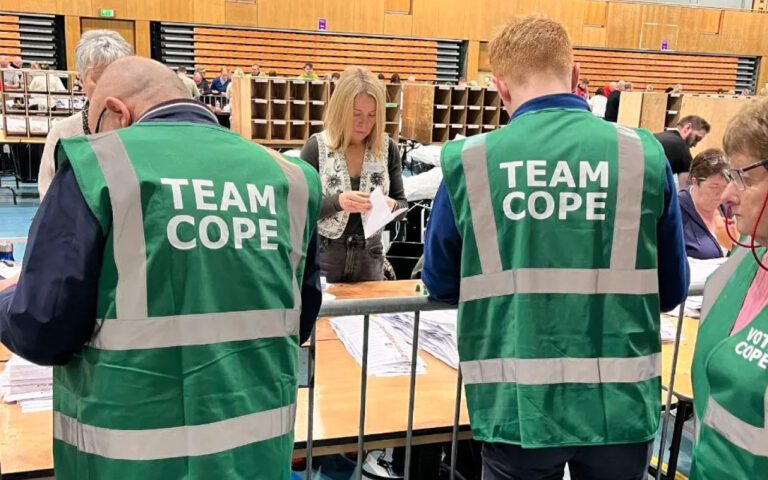

This is compounded by the fact that you have a social media environment dominated by cranks who tend to sensationalism and clickbait. This can manifest in both delusional optimism and conspiracies that encourage a sense of hopelessness. The delusional optimism comes with amplifying isolated cases of rage against the system into popular social media content: the people have woken up; logos is rising; wokeness has been defeated, soon the elites will be on trial for their crimes against the people. And it follows that if the people have woken up, they’ll be happy to vote for any tracksuit-wearing, selfie stick-waving independent who calls himself a patriot, even with no real work gone into a campaign. But when the sobering results come in, the cranks jump to comforting lies. After the Irish election, conspiracy theories abounded social media alleging election rigging. No real evidence was presented, and none were very convincing, but there is a segment of the right that will always go for the theory of maximal regime evil regardless of the facts.

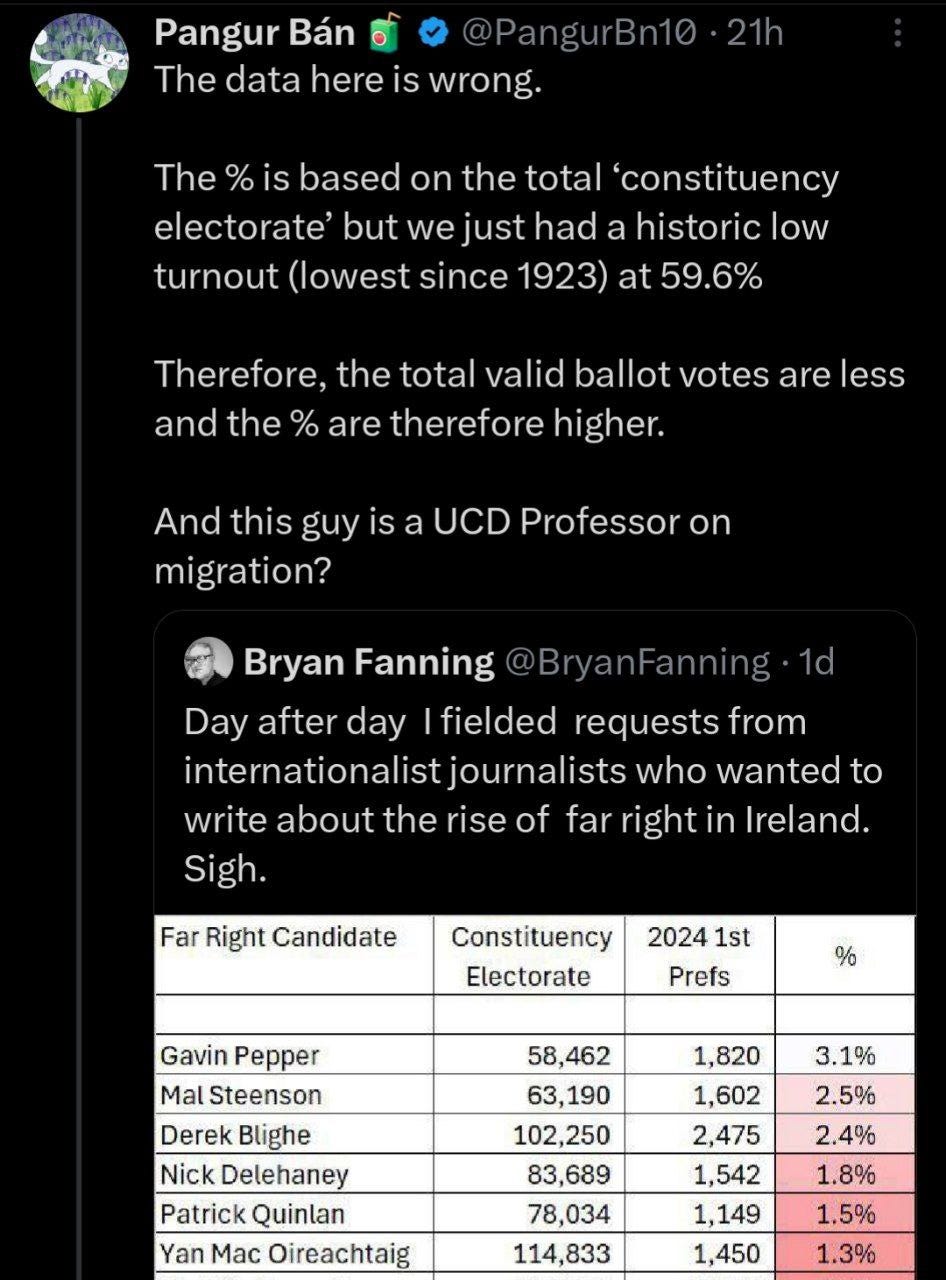

This is the problem with the decline in quality on the right, and why I have been so forceful on the need to be intolerant of schizos and cranks. People generally tolerate them because they think it doesn’t matter if our side believes some untruths if they’re at least “directionally accurate”. But when you allow this to fester, and it becomes impossible to have a sober analysis or your own sides failings, it also becomes impossible to bring them with you improving on those failings. In this particular case, we ended up with a situation where both far-left activists and far-right voices were pushing the same message: if you’re a nationalist, voting is pointless. Leftist activists rushed to social media to post often misleading graphs about how low nationalist vote share was, the point being to demoralise their enemies as much as possible from engaging in politics.

But take a step back from the grim demographic realities we face and just look at the raw numbers of votes, and it’s not as bad as it may have first seemed. The Flare:

This results in a #TotalNationalistVote share of 2.7% nationally and in the five Dublin city constituencies this rises to 6.4% with Dublin North-West coming in at a staggering 9.8% which is 5x greater than 2020.

In this election, the quality of candidates still left a bit to be desired. Many were unknowns in their constituency prior to putting their name forward for this election, some had no real campaign to speak of, let alone a large team of campaigners, and none had the boost of a political party with a voice on radio and television to present as a serious alternative (most of the electorate still decide their vote based on traditional media), and many ran in an area with another nationalist candidate or candidates competing for the same small share of potential voters.

Consider the long road Sinn Féin had to gaining legitimacy in the south of Ireland. Nationalists are reviled by Official Ireland today, but so were Sinn Féin fresh off The Troubles when they were still viewed by most as the political wing of the Provisional IRA. They received 1.9% of the vote in 1992; under 2.5% in 1997; 6.5% in 2002; 6.9% in 2007; 9.9% in 2011, 13.8% in 2016, and finally, in 2020 they became the most popular party in Ireland with 24.5% of the vote.

The real story of this election

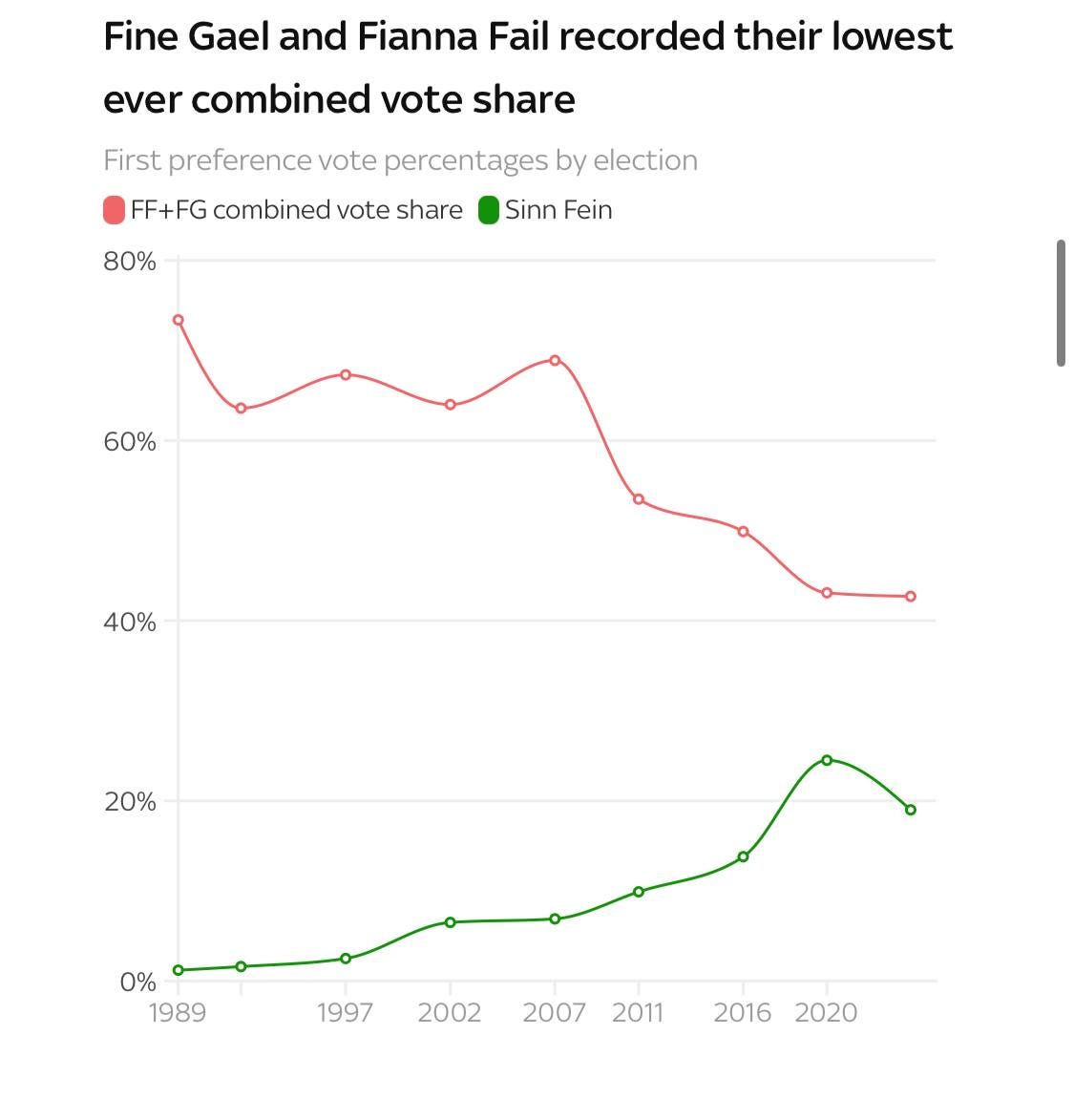

This election had the lowest turnout in a century. Only half of 18-34 year olds voted, but over 90% of the over 60 age category voted. So this election was largely determined by old people who have voted for the establishment parties all their life and value the “stability of” Fine Gael/Fianna Fáil over the alternatives. Despite this, FFG actually had their lowest share of the vote ever, with Sinn Féin also declining:

With any meaningful differences between Fine Gael/Fianna Fáil gone and them now set to be regular coalition partners, Irish general elections are now a referendum on how the ruling uniparty party is governing. Since older people get their news from traditional media, they see the only choice as the stability of the FFG centre or empowering the collection of hard-left parties in opposition. Immigration was a concern, but all the main parties hardened their rhetoric leading up to the election to retain support. So, for most of the populace, the general election is a referendum on the stable progressive centre vs. the radical left in whatever flavour you prefer: the more communist People Before Profit; the more environmental Greens; the more bourgeois and friendly Social Democrats; the more serious-about-governing Labour Party. With how hegemonic progressivism has become in Ireland, these could also form their own left-wing uniparty without any having to sacrifice much on policy.

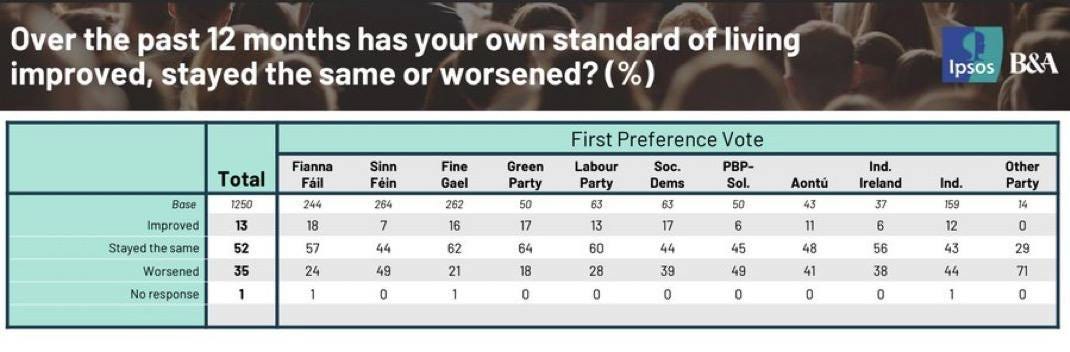

For all the legitimate criticism there is to be levelled at the FFG progressive-centre, a lot of people are doing very well under this government. Ireland has near full employment, massive foreign direct investment, and rebounded from the 2008 crash under these parties with record economic growth. Most of the big issues like housing only really affect the young, and many of them emigrate. If you’re an older homeowner that’s worked your whole life, life in Ireland is pretty good right now, and the value of your property is soaring. Polling after the election shows an economic division, with most supporters of FFG reporting a decline in their living standard under this government to a much lower degree than those voting for alternatives.

In spite of the narrow choice presented in traditional media, Gript’s Matt Treacy calculated the broader anti-establishment but not left-wing vote to be about 300,000 this time around, or 13.65% of the vote. This didn’t translate into as many seats as smaller left-wing parties got with a lower share of the vote, because leftist voters tend to transfer more to other leftist candidates, meaning their vote can effectively count two or three times, and because the vote on the right is so split across candidates, pointing again to the need for a more unified alternative.

One of the biggest problems for an anti-establishment political force is its people with populist sympathies that are most likely to not vote. The attitude of people opposed to all the major parties, or with a taboo view on something like immigration is that voting is pointless given their complete control of the system (another reason why it’s so counterproductive for our own people to encourage hopelessness and promote election rigging conspiracies). If you are voting for FFG or Sinn Féin, your preferred candidate is almost certainly in contention for a seat, but voting for a nationalist candidate likely to get two or three percent feels pointless to a lot of people.

All this is to say that if there was one political party which was representing the nationalist alternative in media and running the single nationalist candidate in most constituencies, there would be a lot of potential for growth. Success breeds success, and as soon as people were actually elected from this bloc and it became seen as a serious political force, many disillusioned non-voters may be willing to lend support to get its candidates over the line.

Certainly, the people are not where we need them to be, but it’s also true that nationalists aren’t capitalising on the nationalist vote that is there. Dublin Bay North, the constituency with the second highest nationalist vote share, had those votes split between six candidates, each with little name recognition. There is really no excuse for this other than egotism and poor organisation.

There is a real lack of quality in the Irish right that is becoming a barrier to progress. Some of the loudest voices only have larger platforms because they post and recirculate topical content so much; the movement is egalitarian to a fault and promotes people that most outside the circle would pass over as unserious loudmouths, cranks and likely welfare cases. People can safely explain away anti-immigration sentiment coming from people that look and act poor as the ignorant resentment of the underclass, and no one wants to be associated with that.

Very few voters look at an election and just vote for the candidate who will represent their view on something like housing or immigration. Irish voters value professionalism and seriousness in politicians, and if someone presents as amateurish or crass most of the electorate will pass over them. Typically, successful nationalist movements grow out of a core of well-organised intellectual ideologues. Consider that Germany’s AfD was established by a cadre of professional economists and other scholars who began by presenting papers critical of Germany’s adoption of the Euro. From there, it moved in a more populist direction winning over disillusioned CDU voters.

The original Sinn Féin movement was led by poets and scholars, men of intellectual brilliance and foresight. The modern populist right that has popped up in Ireland in recent years is a far cry from this: little organisation or willingness to engage aside from big protests which achieve little, anti-intellectual, and dominated by cranks who have adopted harmful aspects of American rightist political culture.

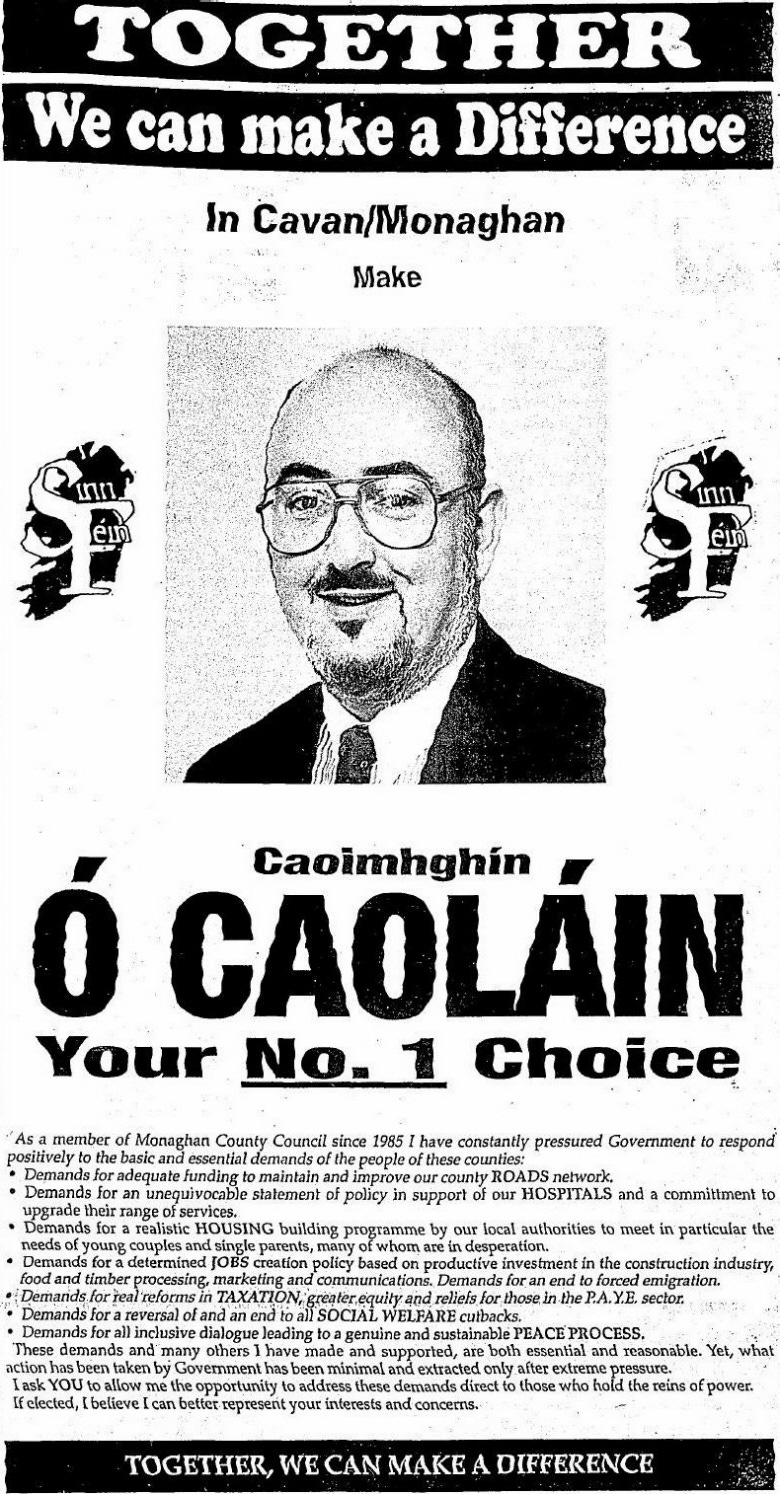

When the modern iteration of Sinn Féin had their electoral breakthrough in 1997, their first TD Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin had already served as a councillor for 12 years, and Sinn Féin had spent years engaging in community politics and building a very strong ground game to prepare moving into electoral politics in the South. Irish politics is still very non-ideological and no candidate is going to be elected just because they voice common frustrations on immigration.

Even while Sinn Féin was a smaller force, it was still able to present a series of alternative, costed policies on everything from housing to capital investment plans. Immigration matters to a lot of people, but not enough to just vote for whichever candidate has marked themselves as the nationalist candidate, and a collection of grievances against the government isn’t enough to get people’s support without a more compelling positive vision. Aontú succeeded a lot in presenting a more conservative message as something that was genuinely a fresh perspective on politics that could improve governance in a number of areas.

But perhaps the best example of success in this election for someone with nationalist views was the re-election of the independent TD Carol Nolan, who topped the poll in her area as an outspoken critic of immigration who takes a pro-life stance. She was originally elected as a member of Sinn Féin but left in protest of their stance on abortion. Only becoming more popular since shows that a critical view of immigration isn’t itself a great barrier to being elected. Nolan, like Helen McEntee, is established in her area and is probably assured of a seat for life no matter what stance she takes on immigration.

This is all to say there is no shortcut to success in Irish politics, but presenting a professional, serious political alternative with an emphasis on community activism will give nationalists the best chance of a breakthrough. The question is, why has nationalism in Ireland up to now been attracting such lower quality people than nationalist movements elsewhere in Europe? How can we remedy this, and begin to win over the competent, intelligent young men who are alienated by the program of Official Ireland? Let me know your thoughts.

This article originally appeared on Keith Woods’ Substack and is republished by The Noticer with permission.

His book Nationalism: The Politics of Identity is now available on Amazon. If you enjoy his writings, please consider purchasing it and leaving a positive review.