Jean-Marie Le Pen, the co-founder of the French National Front — now called the National Rally — died today at age 96 “surrounded by his loved ones,” the family reported. He was a great Frenchman, a patriot who served his nation all his life. He was hated by the French Left and reviled by the “respectable” Right, but he built a party that now may have more popular support than any other in France. In 1998, I was lucky enough to meet Mr. Le Pen in one of my most memorable experiences as an advocate for our people.

Le Pen’s nickname was Le Menhir. This is the French word for the prehistoric standing stones that dot northern Europe. The name evoked Le Pen’s granite resistance against attacks of all kinds.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Le Pen was active in conservative and monarchist circles, but his rise to prominence began when he co-founded the National Front in 1972 with Francois Duprat. Duprat, whose goal was to bring all conservatives under a single banner, was assassinated in a car-bomb attack in 1978. Le Pen himself was the target of an assassination attempt in 1976, when a bomb went off in his Paris apartment, seriously damaging the building. Le Pen was not home. No one was ever arrested for the crime, nor did any group claim responsibility, but far-left fanatics hated Le Pen’s unwavering nationalism.

From the beginning, the National Front firmly opposed mass immigration, and this earned Le Pen the label of “far-right” and “racist.” I will not try to cover anything like his long and distinguished political career, which included five runs for president of France, 10 years in the French Chamber of Deputies, and 24 years in the European Parliament. He consistently campaigned for national sovereignty against the European Union, secure borders, and what he called préférence nationale, or putting Frenchmen first.

I was fortunate enough to meet Le Pen in 1998, when I visited France for the Front’s annual Bleu Blanc Rouge (blue white red) festival. It was a marvelous experience: 100,000 patriots from every corner of France gathered to honor their nation, their movement, and their leader. It was a dazzling combination of political rally, food fair, outdoor market, lecture series, and rock concert, all on fairgrounds at the edge of Paris. More than 100 booths tempted festivalgoers with literature, music, activism, and regional delicacies. Many people spent hours at the festival, where they had lunch and dinner.

Le Pen circulated through the grounds, greeting activists, tasting regional dishes, and signing books — always surrounded by admirers. He shook thousands of hands, and rewarded lady well-wishers with French-style kisses on both cheeks. He was perhaps the most charismatic man I have ever met.

The highlight of the festival was his “great patriotic discourse” on Sunday afternoon. He mesmerized an audience of 20,000 for an hour and a half. I was moved by his invocation of ancestors:

It is the blood of our fathers that flows in our veins — the same blood that flowed to defend France and make it great. Our lives are embedded in this land, which our fathers preserved and improved. It is their language that we speak. When we eat of the products of the land — symbolized by bread and wine — we commune with our fathers by partaking of our nation, both material and spiritual. And when our souls depart this world below, it will be within the maternal soil that our bodies will repose.

His stirring conclusion brought the audience roaring to its feet:

Because I believe that men are creatures of God, I believe they have a transcendent duty, an immense debt to those who have given them life, and endowed them with the spirit of love, beauty and harmony in one of the most beautiful countries on earth. They have a scared duty to their children to whom they owe, on pain of treason, the preservation of this heritage. And they have a duty to all of humanity and to their own history to testify to the greatness and nobility of their fatherland. Long live the free nations of a European Europe. Long live the peoples of Europe. Long live the Front National. Long live France!

Together with Tom Dover of the Council of Conservative Citizens, I had the honor of presenting Le Menhir with a Confederate battle flag that had flown over the South Carolina state house. He accepted it with great warmth and appreciation.

I will never forget the awe I felt for a movement the like of which Americans can only dream, even now. And I well remember how I laughed at the way Le Monde, the lefty French “newspaper of record,” sniffed at the festival: “an angry village of Gauls with a siege mentality and paranoid reflexes,” an “island well outside the ordinarily agreed-upon ethics of democratic debate.” The sneering only made Le Pen’s achievements that much more remarkable.

Le Pen was proof of what a great man can achieve. He attracted fervent support from every part of the nationalist right: monarchists, traditional Catholics, anti-Communists, pagans, and Vichy sympathizers. He was a vehement critic of de Gaulle’s policies, especially his betrayal, as Le Pen saw it, of Algeria, but many Gaullists joined his movement. All set aside their differences to follow a man who spoke so passionately for France.

Of course, Mr. Le Pen made mistakes. He was disqualified from running in the 1999 Euro-elections because of an earlier brush with a socialist that got slightly physical. He unwisely decided that in his place, he would appoint his young and relatively recent second wife, Jany, at the head of the Front’s electoral list. Jany was charming but had never held office, and many party members scorned Le Pen’s decision. This and other matters led to a very nasty split, with the Front losing some of its most capable men.

However, the Front survived, and Le Pen’s electoral eligibility was restored. In 2002, he managed a staggering breakthrough when he came in second in the first round of the French presidential elections in a fragmented field. This qualified him for the second round against incumbent Jacques Chirac, an achievement that terrified the entire European establishment. The full French political spectrum, from center-right to far left, united to crush him, leaving him with only 17.8 percent of the vote in the second round. However, Le Pen had proven that an outspoken nationalist could shake the political foundations of a major European country.

Le Pen was always a brawler — a verbal brawler after he gave up the street-fighting of his youth. He constantly pushed the limits of what he called France’s “liberticide” anti-free-speech laws, and was convicted at least 25 times for inciting racial hatred, anti-Semitism, and holocaust denial. Perhaps his most famous case of “hate speech” was to have said, in 1987, “I’m not saying the gas chambers didn’t exist. I haven’t seen them myself. I haven’t particularly studied the question. But I believe it’s just a detail in the history of World War II.” He also doubted the Nazis killed as many as six million Jews.

Comments like this irritated his daughter Marine, who had become head of the party in 2011. Other members thought the brawler had become a liability to a party that was trying to “detoxify” and “rebrand.” In what must have been one of the bitterest moments in Jean-Marie’s life, the party suspended and then expelled him in 2015. Three years later, in an attempt further to distance the party from its roots, Marine changed the name from the National Front to the National Rally.

Marine Le Pen went on to take the party to heights never achieved under her father. She advanced to the second round of French presidential elections in 2017 and 2022, though was defeated both times by Emmanuel Macron. In 2022, she won a very respectable 41.5 percent of the vote. Opinion polls consistently put her at first place for the 2027 election. Depending on the metric used, the National Rally is considered the most or second-most popular party in France.

Many attribute this success to Marine’s softening of her father’s positions, but her party is still treated as a pariah. Even now, she would probably face a left-right coalition to keep her out of the presidential palace. It is impossible to know whether the National Rally’s success is due to Marine’s more moderate tone or to a rising national/racial consciousness among the French and Europeans in general.

Fortunately, there was reconciliation between father and daughter, especially in 2018 when Jean-Marie was hospitalized. Later that year, all three daughters were present to celebrate his 90th birthday.

Jean-Marie openly supported Marine’s 2022 run for president.

Let us hope that this great man, whose health had been failing for some months, died in peace. He loved France and its people with all his heart, and in death, countrymen who never voted for him seem to recognize this.

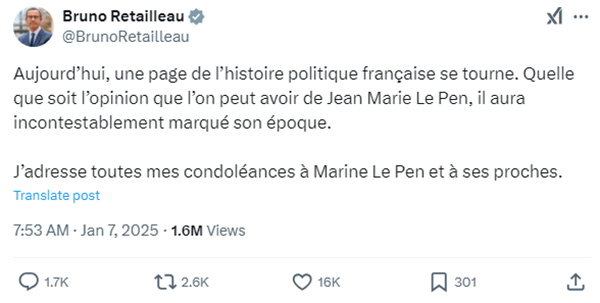

Bruno Retailleau, current Minister of the Interior under Le Pen-hostile Emanual Macron posted this:

“Today, a page has turned in the history of French politics. Whatever one’s opinion of Jean Marie Le Pen may be, he will have undoubtedly left his stamp on his era. I extend all my condolences to Marine Le Pen and her loved ones.”

Jean-Marie Le Pen fought the Great Replacement before it even had the name — given to it by another far-seeing Frenchman, Renaud Camus.

I count myself blessed to have been able to shake his hand, look him in the eye, and tell him how much I admired him. May we have many more men like him.

Header image credit: Jared Taylor and Tom Dover of the Council of Conservative Citizen presenting Le Pen with a Confederate battle flag (American Renaissance).

This article originally appeared on American Renaissance on January 7, 2025, and is republished by The Noticer with permission.