The medieval formation of a German national identity

In a previous essay, I looked at the shaping of an Italian national identity within the early Roman Empire, and argued, contra modern scholars, that an ethnic Italian identity based on shared ancestry was well developed within the Roman Empire, and remained a source of pride throughout its existence.

The presence of this kind of primordial nationalism in pre-modern empires seriously undermines the claims made by the modernist school of thought in the sociology of nationalism, which is treated as orthodoxy in many sociological departments in the West.

To recap, modernist scholars argue that nationalism is a product of the modern age — a false consciousness imposed on the masses to homogenise mass populations for the purposes of modern economics and governance. Modernists typically argue there was no nationalism prior to the French Revolution (some date it even later), and prior to this more local, religious and imperial identities were the norm.

To show that national identities which conform to the nations we recognise today existed in pre-modern empires would be devastating to the modernist argument; and doubly so if it was felt among the masses of common folk prior to the emergence of the bureaucratic state. To this end, there is no better example of an empire that represents the medieval form of governance than the Holy Roman Empire, which dominated central Europe for a thousand years.

What was the Holy Roman Empire?

Voltaire famously quipped that “The Holy Roman Empire was neither holy nor Roman, nor an empire.” Though learned historians can take issue with each one of these, the quip has outlasted the Empire, capturing what a bewildering entity it has since seemed to those approaching it with our modern understanding of sovereignty and statecraft.

The Holy Roman Empire was never one unified state, but neither was it a confederation of states. Unlike other monarchies, it never had a written constitution. Its territory was never clearly defined: the borders between the empire and its neighbours were not clear, nor were the borders between the duchies, counties, city-states, margraviates and other entities which composed it. The Empire had no central government, bureaucracy or army, and no recognised supreme sovereign — there were regular disputes over sovereignty between the empire and local princes and rulers.

The HRE was a loose affiliation of many semi-sovereign entities bound by all sorts of formal and semi-formal oaths, loyalties and historical connections. So what was the imperium this affiliation, at least nominally, existed under?

Charlemagne, the king of the Franks, was crowned emperor by the pope in the year 800, thus transforming his claim from ruler of one Germanic tribe to a universal ruler continuing a lineage coming from the Roman Empire.

The title of emperor was revived by Charlemagne’s descendant Otto the Great, and was maintained by all succeeding imperial rulers, allowing the German kingship to claim approval by the Church as well as succession from the Roman Empire, and thus imperium over all European and Christian rulers.

The Germans that composed the majority population of the HRE developed Romanising myths that explained how they became the rightful inheritors of the Roman legacy. One such myth claimed that the Germans had aided Caesar in his struggle with the Senate for supreme authority.

Germans also embraced the doctrine that there had been a binding ‘translation’ of the Roman Empire to the German people. Four centuries after Charlemagne’s coronation, Pope Innocent III made this doctrine canon when he published the Venerabilem in 1202. Innocent explained that the Holy See had translated the Roman Empire from the Greeks to the Germans in the person of Charlemagne.

Despite the claim to be a continuation of Rome, neither Italy or the Church had any say in who actually ruled the HRE. Its emperors were exclusively German, were coronated in Germany, and from the 13th Century onward, were chosen by German prince-electors in an Imperial election.

Practically, the “universal imperium” of the Holy Roman Empire comprised what today encompasses three nations: Gaul in Northeast France, northern Italy and Germany. But by the late Middle Ages, the German character of the empire became more pronounced, as it lost control over non-German regions in Italy and Burgundy.

The Empire also embraced a policy of Germanising the Eastern regions of the Empire populated by non-Germans. This included large scale settlement of Germans, who rulers sometimes made way for with expulsions of previous, non-German inhabitants.

By the 15th century, the empire had adopted the full title of “The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation”, and after this period “the German Nation” was often used interchangeably with the title of Holy Roman Empire.

In this period, the connection between the emperor’s title and the Holy See was also severed. King Maximilian I was the first to start calling himself an “elected emperor” in 1508, without a coronation by the pope, something which soon became the norm among his successors, who began presenting the result of these elections to the pope as a mere formality.

A German historian, Georg Schmidt, uses the phrase ‘komplementärer Staat’, or ‘composite state’ to refer to the structure of the HRE. Not quite the centralised, bureaucratic state we are used to today, but also more than a series of alliances between its composite parts.1

Rather than with the emperor or the individual ruling nobility, sovereignty was vested in the imperial composite state itself, and this state was increasingly identified with the German nation. It was a nation much less politically unified than, say, the French or English nation, but there was no question in the minds of its inhabitants that it existed.

This seriously undermines the claim of modernist scholars of nationalism that national consciousness is something manufactured by states. Ernest Gellner had written that nationalism required:

The general diffusion of a school-mediated, academy supervised idiom, codified for the requirements of a reasonably precise bureaucratic and technological communication. It is the establishment of an anonymous impersonal society, with mutually sustainable atomised individuals, held together above all by a shared culture of this kind, in place of the previous complex structure of local groups, sustained by folk cultures reproduced locally and idiosyncratically by the micro-groups themselves.2

But what better example of a structure which maintained local and regional autonomy and folk ways than the medieval empire par excellence that is the HRE? And yet without a centralised state, homogenising bureaucratic norms, an atomised individualist society, or a state mandated universal education, the German nation emerged and endured across the many polities that composed it.

The Germanisation of the Reich

The beginning of the 16th century marked a turn in the HRE. After the “Diet of Worms” in 1495, a more institutionalised structure to government was developed and became more distinctively German than the imperial structures they replaced.

This included the founding of the Imperial Chamber Court (the Reichskammergericht) as well as the organisation of the imperial diet itself (the Reichstag), a forum for negotiation between the estates of the Reich. In the words of one German historian:

If one criterion of the modern state is increased bureaucratization and institutional consolidation, then the tum of the fifteenth to the sixteenth century clearly represented a deep watershed for the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.3

The development of more characteristically German political structures occurred in tandem with a more explicit identification of the Reich with the German nation:

From the fifteenth century, writers of various political hues invoked the superior rank and dignity of the Empire, a shared historical past, and notions of German liberty which, depending on the individual viewpoint of the person concerned, resided with the emperor or the Estates respectively, in order to establish a close link between the Reich and the German nation.4

Part of the discovery of this German identity involved a closer engagement with early German history. Renaissance humanist scholars looked to early sources to trace the history of the German people, particularly Tacitus’ Germania.

The Renaissance scholar Conrad Celtis implored his fellow Germans in an address to the Bavarian University of Ingolstadt to put learning to the service of the German nation, particularly searching ancient sources for information about Germany:

Celtis’ electrifying speech at Ingolstadt focused on the Germans’ common qualities. His main theme is that the Germans constitute a single Volk, itself divided into tribes. The first Germans, as “our Tacitus” assures us, were indigenous. Indeed they were the world’s only unmixed ethnic group, then or since.5

Celtis’ own contribution to this was releasing his own edition of Tacitus’ Germania. Although ancient Germans were much more divided than Tacitus’ scholarship reflected, the German humanists embraced this work as demonstrating the ancient unity of the German people.

At the same time, German geographers began to make detailed maps of “Germania” the region identified by Tacitus as home to the indigenous Germani people: its natural borders being the Rhine to the west, the Danube to the east, and a great ocean to the north.

This rush to define the German national character was also motivated as a response to Italian humanists who viewed Italian culture as superior, and as a rebuttal to Pope Pius II, who, in 1455 used a copy of Germania to implore German princes to launch a crusade on the Turks, using the work to demonstrate that the Church had civilised the historically barbarous Germans.

While Italian humanists used Roman sources to portray the aboriginal Germans as “uncouth, beer-guzzling idol worshipers, who sat around gambling and slugging each other”6, the German humanists found much to be proud of in the descriptions of Germans as a proud and independent people who loved their freedom, prized loyalty, and made formidable military foes to the mighty Romans.

A special source of pride for Germans was their success in battle and the heroic qualities of their warriors, with celebrated rulers being mythologised as “hero” or “mighty warrior”7.

Over time, they came to find so much of value in their ancient forebears that they saw Germany as equal or superior to ancient Rome and contemporary Italy.

The German jurist critique of Empire

A more moderate proponent of the modernist thesis might argue that although there was something like a German national consciousness in the later HRE, since this national consciousness did not result in the demand for a nation-state it can’t properly be called nationalism. Gellner elsewhere defined nationalism as “a political principle which holds that the political and the national unit should be congruent”,8 and, although national identities predate the 18th century, it is only by the late 18th century that the idea that a nation-state should represent the nation emerges.

A good rebuttal to this is provided by a number of German jurists from the 17th century, who critiqued the very notion of a Holy Roman Empire on the basis of it either failing to properly represent the German nation, or making a claim to land it had no natural right to.

In 1642, a short book titled ‘A New Discourse on the Roman-German Emperor’ was published by a jurist named Hermann Conring to investigate the imperial claims of the HRE and its connection to the Roman Empire. More specifically, Conring sought to answer the question of whether the Roman Empire still existed, and whether the HRE was its continuation. He answered in the negative:

Since the Eastern Roman Empire has long since been destroyed by the Turks and hardly anything of the Western Empire is left to our emperors except the imperial title, it is perhaps not wrong to affirm that either the Roman Empire has perished completely or, if you put aside the question of whether or not the papacy had the right to usurp the imperial title and confer it on others, that the imperial power is actually in the hands of the Roman Pope.9

The Eastern part of the Roman Empire had been destroyed by Turks, and of the Western remnant there was nothing left but imperial titles. At most, you could argue those imperial titles were properly inherited by the papacy.

The relevant conclusion, though, was that the German empire had no claim to succession from Rome, and neither Italy nor Germany had any natural right to rule over one another:

Only one monarch had the right to rule Germany, and that was the king of Germany. If the king of Germany happened to be elected Roman Emperor as well, that was just fine, but though it added a certain touch to his dignity, it added nothing at all to his rule over Germany. Germany and Lombard Italy were sovereign states ruled by their own kings. They did not belong to the Roman Empire and they were not subject to Roman law.10

Anticipating how uneasy it might make subjects of the Empire to undermine its centuries old claim to Roman succession, and how subversive this might seem in undermining the sovereignty of the existing emperor, Conring reassures them the emperor’s right to rule remains just as the sovereign ruler of Germany, no connections to old, foreign empires are required:

If ever since the eighth century all other states have yielded first place to Germany and its kings or emperors, they surely did so with good reason. Since this dignity and the privilege of the first rank stem not so much from the imperial title as from the real extent of the Empire, and since Germany’s possession of this honor has not been contested up to now, the rights of the German kingdom will remain intact even if you take the name of Emperor completely away.11

The right to rule Germany now resided with the Germans, and they could sever their connection with Rome once and for all.

Conring was joined by Samuel von Pufendorf, one of the most influential scholars of 17th century Germany, in critiquing the old imperial structures.

If Conring was focused on the technicalities of German imperial claims, von Pufendorf was far more scathing in attacking the poorly organised imperial structure. In 1667, von Pufendorf caused a sensation when he pseudonymously published a political tract titled ‘On the Present State of the German Empire.’

In the text, von Pufendorf calls the German Empire “an irregular body resembling a monster.” von Pufendorf critiques the uneasy arrangement where the estates and monarchy compete for power as undermining the stability of the empire itself, often to the detriment of German national unity:

Germany is so weak because two evils converge in it: a poorly organized monarchy and, at the same time, a disordered confederation of states; the main evil is that neither form of government fits Germany.12

Not only is Germany divided by the estates, but they themselves are divided by multiple forms of government and mutual suspicion.

This even leads to the absurdity, as Pufendorf sees it, of German estates allying with foreigners in conflict with other Germans. He also notes that:

Religion, otherwise the strongest bond between minds, has torn Germany into factions and immersed it in violent conflicts.

Tragically, were Germany to be united under one monarchical constitution, von Pufendorf claims its “greatness and strength could be a threat to all of Europe”.

A century later, a German jurist named Friedrich Karl von Moser published a much discussed pamphlet On the German National Spirit.

Unlike von Pufendorf, von Moser was proud of the institutions of the Reich, which had given Germany its place among the most powerful nations of Europe. On the existence of a German national identity, he was emphatic:

We are one people, with one name and language, under one common head, under common laws that determine our constitution, rights and duties, committed to a common great interest in freedom, unified to pursue this purpose in a National Assembly that is more than one hundred years old, Europe’s premier empire in terms of internal power and strength, whose royal crowns gleam on German heads.13

Two writers, one century apart, one highly critical of the “monster” Empire, one a proud defender of the institutions. But for neither was there any doubt that this was a German empire, and in each case the success or failure of the government was judged on its ability to serve the German nation and increase its power in the world.

Though a unified Germany would not come for another century, debates were already ongoing about whether a unified national state was needed to best serve Germany or the HRE sufficed.

If nationalism is a political principle which holds that the political and the national unit should be congruent, then it’s clear that this principle was taken for granted by these German intellectuals.

A common response modernists make to this kind of argument is to say these attitudes were confined to intellectuals and the upper class. Only after industralisation and the spread of universal education did these high culture ideas of nationhood translate to the masses by indoctrination.

But this is disproven by how often German princes found it expedient to appeal to the German patriotism of their people. In 1673, Leopold I made appeals to various rulers to defend “the Holy Roman Empire, the liberty of the German nation and the interest and welfare of its individual members”.14

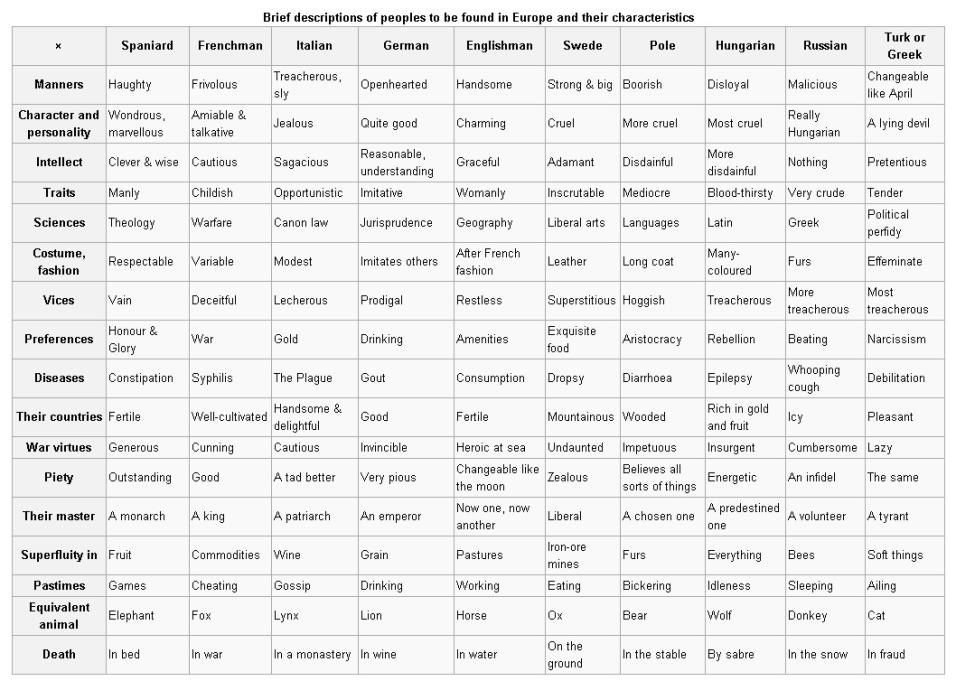

The Styrian Table of Peoples, created in Austria in the early 1700s, depicts 10 different European peoples based on popular ethnic stereotypes of the time. The distinctions are quite detailed; from the science each nation excelled in (jurisprudence for the Germans, warfare for the French) to what diseases they were supposedly prone to (whooping cough for the Russians, constipation for the Spaniards).

For a people that, according to modern sociologists, were only concerned with local and regional folk identities, the people of this time seemed to give great thought to the ethnography of European nations, and these nations are still what we recognise as the major national groups in Europe today: Spanish, French, Italian, German, English, Swedish, Polish, Hungarian, Russian and Greek.

Historians can quibble about whether the Holy Roman Empire was truly holy, Roman, or an empire, but what cannot be doubted is it was German.

By the time most Europeans were referring to the Holy Roman Empire as the German nation, its inhabitants already had a strong sense of German national identity. When the Empire was finally dissolved in 1806, and little popular identification with the old monarchy or its hundreds of smaller entities remained, the German nation endured.