Civil war is on people’s minds a lot lately. After the failed assassination of Donald Trump in July last year, many commentators remarked that the US had been an inch away from a civil war. This was followed by an explosion of social unrest and rioting in England over the butchering of three young children by a Rwandan immigrant, which similarly had people proclaiming that the UK would descend into a state of violent conflict.

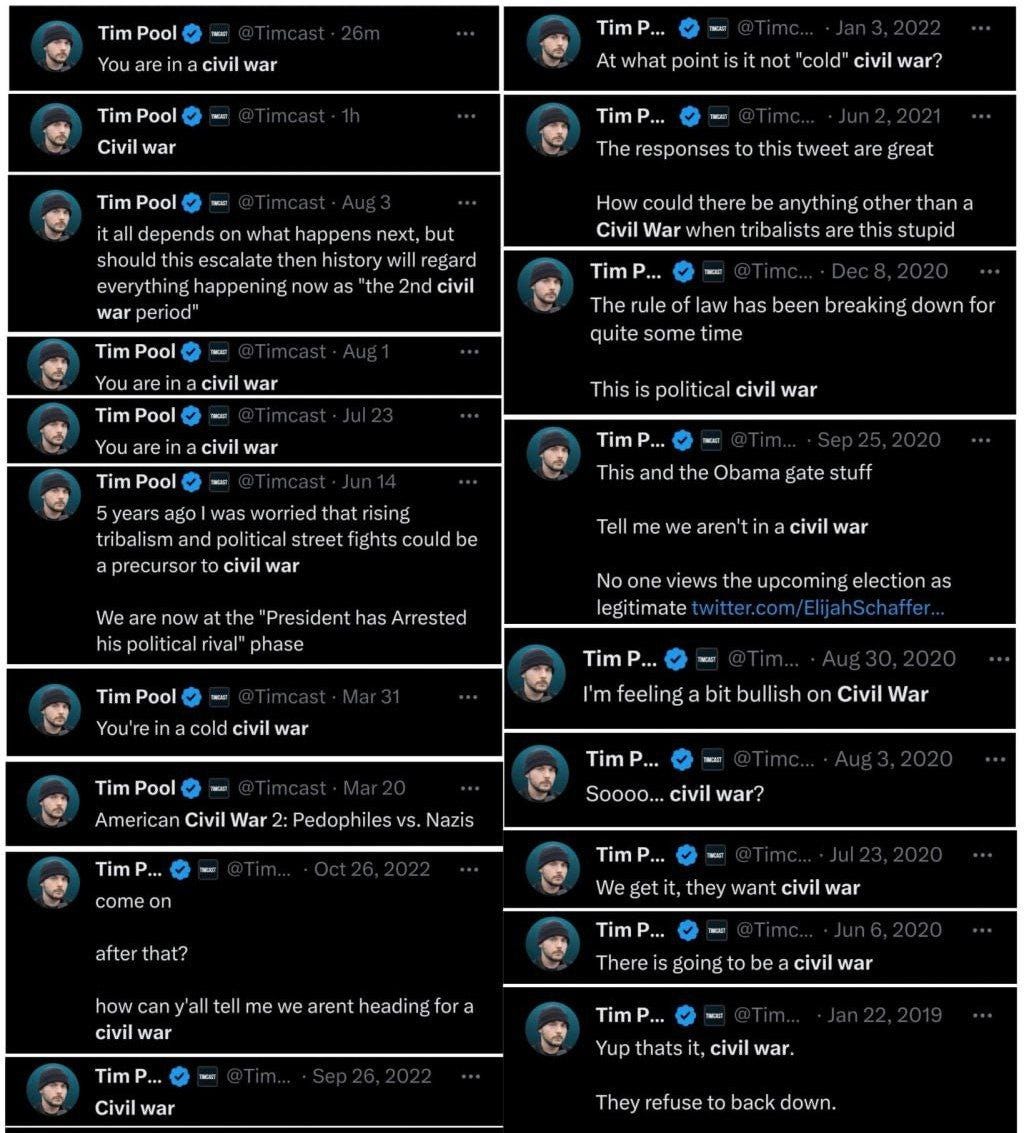

Of course, anyone familiar with the subculture of right-wing politics will know that predictions of an imminent revolution or civil war are par for the course, with any expression of social unrest catastrophised and presented as a harbinger of imminent conflict.

The right-wing collapse fantasist has a theory of revolution that goes something like this: politics gets really polarised, conditions become intolerable due to the radical policies of the regime, eventually there is a big event — an economic collapse, a stolen election, an attempt by the government to seize people’s guns — and this triggers the right-wing section of the country to erupt in revolt. Of course, since the conservatives have the guns and tough guys on their side, they win easily against the limp-wristed liberals, and then all our political problems can be solved overnight in a new regime free of the constraints set by the old regime.

To be fair to these people, believing a civil war is on the horizon is not exactly a niche opinion. A 2022 poll found that 43% of Americans thought a civil war was at least somewhat likely within the next decade. More recent polls have put that number over 50%. Establishment academics and journalists have also begun to sound the alarm for a potential conflict that could tear the United States apart. Canadian journalist Stephen Marche argued in his 2022 book, The Next Civil War: Dispatches from the American Future, that another American civil war is now inevitable. “The United States is coming to an end. The question is how.” A book published the same year, How Civil Wars Start: And How to Stop Them by political scientist Barbara F. Walter — a consultant for the US Department of Defense and the January 6th Committee — made similarly gloomy predictions.

Capitalising on the zeitgeist, Hollywood produced its own dystopian thriller titled ‘Civil War’, set in a not too distant American future where the country is split between a tyrannical federal government and a number of large regional secessionist factions.

Clearly, it’s not just kooks on the internet that feel like a real conflict is around the corner. Still, I think the chances of one are much overblown. Despite some very visible social unrest, we are still far from a real conflict.

What causes a state collapse?

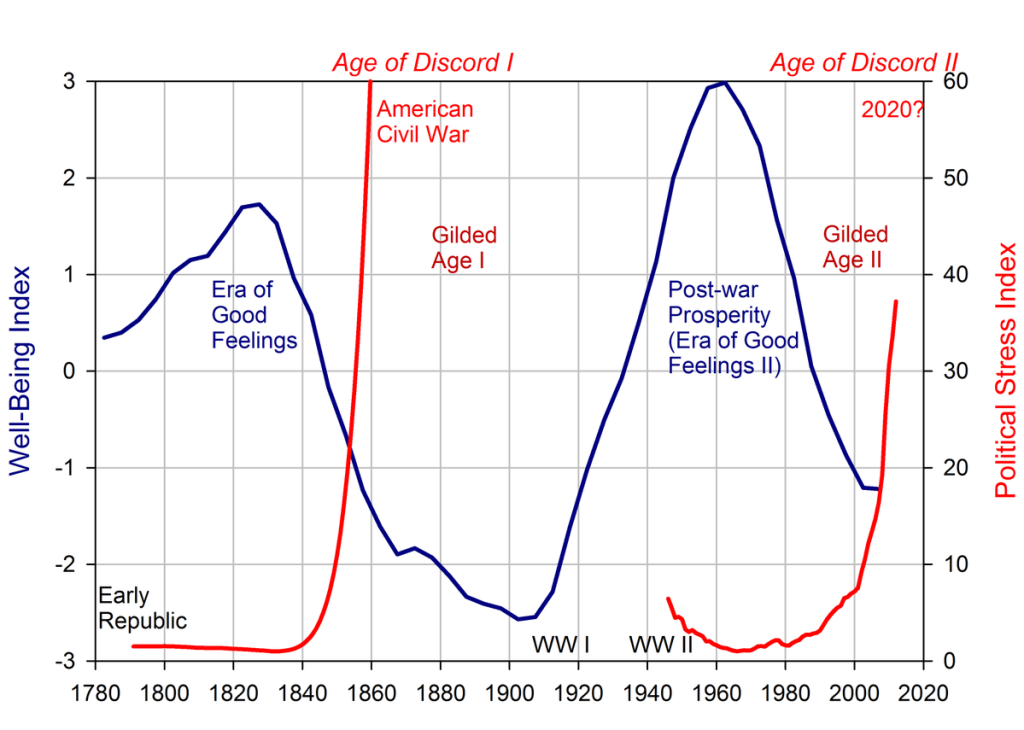

One of the most interesting ways of analysing political history is through structural-demographic theory, which treats societies as complex dynamic systems and uses mathematical modelling to predict instability and collapse.

In recent years, the Russian scientist Peter Turchin has popularised a version of this theory, positing a theory that can accurately predict state collapse. The theory comes down to Turchin’s formula for measuring a country’s “political stress index”. This is the formula:

Political Stress Index = Mass Mobilisation Potential (MMP) x Elite Mobilisation Potential (EMP) x State Fiscal Distress (SFD).

Essentially, you need masses of people in a state of discontent, generated by “popular immiseration” and declining living-standards, ready to support radical challenges to the state and a class of frustrated would-be elites who can organise this mass-mobilisation potential into a revolution.

These elites come about through “elite overproduction” — too many elite aspirants for too few positions of power. Lastly, the state being in distress financially makes the prospect of a revolution more appealing than the alternative.

Turchin’s model predicted that the 2020s would be a time of turbulence for the United States, with an increase in political violence and riots. Having now emerged from COVID-19, the summer of Floyd, and the contested 2020 election, it seems the predictive power of his theories are vindicated. Throughout this period, I recall people on the right making confident predictions of a descent into civil war.

If half the country thinks the regime just cancelled democracy and installed a dictator, surely that would be enough to start conflict, right? Of course, both predictions were way off the mark. BLM rioted for a summer, then it faded out and everything just got a bit more left-wing and black people were policed less. The closest thing to mass political violence that came from the 2020 election was January 6th, which ended with a couple of people dead and everyone involved rounded up and arrested. Then business as usual continued.

On paper, you can see why someone would be more confident that Western countries are on the precipice of civil conflict. After all, more Americans than ever now say political violence is justified against their enemies. Almost 70% of Republicans think Joe Biden’s election was illegitimate, while a 2021 poll found that 2 in 3 Southern Republicans were willing to express support for a secession from the United States. Why is it that despite social unrest and historic political polarisation, the regime remains relatively stable? Because a lot of people being very disaffected with the current system does not translate to a real conflict unless there is a similarly serious defection of elites.

With the liberal view of history we are handed down, we tend to accept the interpretation of political revolutions and civil wars as quite democratic affairs — a spontaneous eruption of popular discontent or a desire for separation. This causes us to overlook how elites and the structural incentives laid out for them shape this mobilisation and create the dividing lines on which the conflict takes place.

The pattern we find which is common to all revolutions, is that it is really a showdown between two groups of elites, one of which already has substantial power, political or economic, but has some avenue of power denied to them. With that said, it’s helpful to look back at some of the great instances of state collapse with a closer eye to how elite incentives shaped events.

How revolutions happen

Revolutions require a condition where the masses are in a state of discontent and willing to mobilise, an elite that is opposed to the ruling elite, and a shared narrative to unite the elite and mass grievances which the alienated elites can use to mobilise the masses.

Without a disaffected elite willing to provide narrative and organisation, it doesn’t matter how hard done by the masses feel, this will only translate to undirected outbreaks of violence and protest which can be easily dealt with by the organisational capacity of the state.

In Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction, the sociologist Jack Goldstone writes:

Poverty is generally not associated with revolution…When the American Revolution occurred, American colonists were far better off than European peasants. Even in Europe, the French Revolution of 1789 arose in a country where those peasants were generally better off than the peasants of Russia, where revolution did not occur until more than a hundred years later. This is because poor peasants and workers cannot overthrow the government when faced with professional military forces determined to defend the regime. Revolutions can occur only when significant portions of the elites, and especially in the military, defect or stand aside. Indeed, in most revolutions it is the elites who mobilize the population to help them overthrow the regime.[1]

A financial crisis — resulting in a cost of living crisis and popular immiseration — preceded the French Revolution. This got so bad that it caused famine and widespread rioting, but as long as it remained disorganised, it did not truly challenge the state. It was only when the already agitated masses were mobilised behind the ideas of liberté, égalité, fraternité by the powerful new bourgeoise, that unrest turned to revolution.

The Estates met in May 1798 to come up with reforms to alleviate the many financial crises of the state, but cooperation broke down between them. The clergy and nobility insisted on voting by Estates rather than their raw numbers, ensuring their votes would always outweigh those of the commoners, or the Third Estate.

However, by this time the Third Estate had developed a powerful bourgeoise — professionals, bureaucrats and wealthy merchants and industrialists — who had for some time been transferring their wealth to political power.

Most of the eighteenth century in France had been a time of considerable social mobility: the so-called “Nobles of the Robe”, which partly composed the Second Estate, allowed members of the bourgeoisie to buy judicial or administrative offices that conferred noble status.

The bourgeoise being denied the full political privileges of the aristocracy was tolerable for a time, but when it meant bearing the brunt of the financial crisis caused by the poor economic management of the older elites, revolution became much more appealing. Social mobility for the wealthy was only partial and limited to a set number of titles while the bourgeoise itself expanded (elite overproduction), and eventually the bourgeoise had all the means at its disposal to remove the old regime. The cost of an attempted revolution was low, the reward was great.

People predicting some kind of American civil war between MAGA supporters and the liberal regime might look to the American Civil War as a more fitting comparison. Here too, there was a clear bifurcation of elites established well before the outbreak of the conflict. As in France, this political divergence was preceded by economic divergence.

The Southern economy was heavily agrarian, with its crop production requiring vast amounts of land and labour, supplemented by slavery and conferring great wealth (and influence) on plantation owners. From the early 1800s, the North began to diverge economically. The war of 1812 with Great Britain disrupted trade and pushed America towards industrialisation. The American government invested in this economic nationalism, building infrastructure, rail, roads and canals, helping turn Northern cities into manufacturing powerhouses. With this came the rise of a new industrial, urban business elite.

As with the French bourgeoise, the new economic elite in America were denied the political influence their numbers should have conferred. The “Three-Fifths Compromise” allowed Southern states to count three-fifths of their slave population when determining representation in Congress.

Just as France’s estate-based voting system ensured the old nobility maintained control over the direction of government and could force the bourgeoise to bear a disproportionate brunt of economic pain, the structures of American government ensured the Southern elites’ disproportionate political power at the same time their economic interests were diverging from the Northern business elites.

Southern elites supported low tariffs, as their agrarian economy required importing manufactured goods from Europe. Northern industrialists, on the other hand, favoured the kind of economic nationalism that facilitated the growth of Northern industry, which included tariffs to protect native industry from foreign competition.

This division among the elites proved irresolvable, even with a series of legislative compromises in the decades leading up to the Civil War, which attempted a balancing act between their incompatible policy demands. By the time of Lincoln’s election in 1860, the Southern elite saw the writing on the wall and became confident enough to finally separate.

Most revolutions follow this pattern. Elites bifurcate, usually due to revolutionary economic or geopolitical shifts creating a new elite class, this new elite gather significant wealth and influence, but is frustrated by existing political arrangements. Eventually, it becomes clear the split cannot be resolved, and popular unrest — usually triggered by a financial crisis — finally gives the savvy among them the opportunity to draw on the masses and foment revolution.

Peasant Revolutions

But what about peasant revolutions? In the cases of the communist revolutions in China and Russia, there does not seem to have been such a clear division in the elites, and each was a much more bottom-up revolt, with communist vanguards organising the peasantry to challenge the state.

Sociologist Theda Skocpol produced a structural model that helps explain these cases of social revolution. The crux of it is that these social revolutions are not set off internally through a mass uprising. Rather, that comes after the state has begun to implode through several structural pressures:

In relatively weak states faced with military or economic competition with stronger states in the context of unevenly developed international economic and political systems. Confronted with military collapse and/or fiscal crisis, the state seeks to strengthen itself through relevant reforms, such as ending the tax privileges of the upper classes or acquiring direct control over the agricultural surplus. [2]

This is what happened in France, which was faced with costly wars and economic crises. But the bourgeoise was powerful and organised enough to block the reforms attempted by the state and make a grab for power. In Russia and China, which were laggards in economic and political development, peasants had a much greater degree of political autonomy, and landlords lacked direct political control at the local level.

In Russia, peasants had a substantial degree of self-government, and the upper class had little direct control over production or the local administrative apparatus. When the state suffered collapse brought on by its costly and failed entry into the Great War, the peasantry could easily become organised against the politically weak landed upper class. The organisation was provided by “surplus elites”, which brings us back to Turchin’s theory of elite overproduction making state collapse more likely.

While communist revolutions were peasant revolts, they were led by middle-class intellectuals like Lenin and Trotsky — the type of people who are excluded from the elite by low social mobility in times of “elite overproduction”.

Of course, once the communists attained state power in Russia and China, they quickly reconsolidated that power and created a stronger, more bureaucratic state that stripped away peasant autonomy and rapidly industrialised. Often, this meant brutal repression of the peasants, ensuring the dissolution of the kind of self-governance that allowed for them to rebel in the first place: just look at Stalin’s brutal war on the kulaks.

This type of revolution was totally at odds with the predictions of Marx, who theorised a communist revolution would come at the far-end of industralisation, in the most industrialised, most capitalist countries, carried out by the proletariat. Instead, it was the political entrepreneurship of surplus elites — middle class intellectuals, who seized on the structural imbalances of states struggling to modernise by mobilising immiserated masses to attain political power.

These social revolutions were anomalous historically, but, crucially for what is being argued here: they were brought on by a series of structural factors unique to states in the process of modernising away from feudal, agrarian societies to modern industrial states. Conditions like this do not exist today, least of all in the Western world. There is no peasantry or landed upper-class, let alone the kind of autonomous communities and local self-governance the Russian peasants enjoyed. No states are faced with the kind of external pressure brought about by geopolitical shocks like a World War.

Where are all the surplus elites?

One aspect of Turchin’s state collapse formula which certainly applies to today is elite overproduction. One of the clearest examples of this provided by Turchin is in the field of law:

From the mid-1970s to 2011, according to the American Bar Association, the number of lawyers tripled to 1.2 million from 400,000. Meanwhile, the population grew by only 45%. Economic Modeling Specialists Intl. recently estimated that twice as many law graduates pass the bar exam as there are job openings for them. In other words, every year U.S. law schools churn out about 25,000 “surplus” lawyers, many of whom are in debt. A large number of them go to law school with an ambition to enter politics someday.

Unemployment and underemployment of college graduates is a common and worsening problem. This, combined with growing inequality and a stagnation of living standards for the majority, is a recipe for instability. Collapse fantasists on the right may hear this and imagine this includes a class of people suitable for a right-wing revolution. It doesn’t.

We need only look at what these surplus elites have done with all their free time. One thing they did was protest for Black Lives Matter. A 2020 article in the New York Times reported on polling of BLM protestors which showed the main difference between them and past civil rights protestors is they were whiter, more educated and more wealthy.

According to the Civis Analytics poll, the movement appears to have attracted protesters who are younger and wealthier. The age group with the largest share of protesters was people under 35 and the income group with the largest share of protesters was those earning more than $150,000.

Half of those who said they protested said that this was their first time getting involved with a form of activism or demonstration

This probably creates dissonance in the minds of many on the right. After all, shouldn’t a “counter-elite” be supporting things that are actually counter to the elite? But of course, most of the elite overproduction is coming out of the left-wing university system, and comprises people whose convictions include the belief that their country being run by rich white men is systemically racist.

The bleak reality is that most of the elite overproduction is going to be directed to more left-wing causes, expressing the consensus of educated Millennials and Generation Z against the more centrist liberal consensus of Boomers.

Things are no better in Europe: a recent poll of university students in Ireland’s Trinity College Dublin found that 63% of them had participated in some form of a left-wing student organisation at college. These are the people who will be agitated to social activism by issues like the housing crisis and underemployment, but it won’t be for a right-wing cause.

Even if there were some kind of revolution from below, Western states are incredibly well equipped to deal with them. Conservatives comfort themselves with the knowledge that “we have the guns”, and this is true, but the state could easily deal with even a sizeable number of these people engaging in armed revolt. For years now, Western regimes have been turning their sights to the perceived threat of the right. In the United States, organisations like the FBI, CIA, DHS are heavily militarised and trained extensively in counter-terrorism. This is not to mention the enormous surveillance capabilities of the modern state, or the capacity to cut revolutionary movements off from the financial system. The disparity of powers is so great it seems absurd to even consider a serious domestic threat emerging to the state. We don’t even know all the techniques at its disposal in the event of having to subdue a large segment of its population, but we know it has directed large amounts of resources to dealing with this possibility.

And, while people will look to examples like the Taliban to show that an ill-equipped insurgent army can defeat a larger foe, this too is misleading. Most insurgencies end in failure. The Chechens, the Syrian rebels, ISIS and FARC all lost, along with countless other examples. The Taliban won because the US made a political calculation that it wasn’t worth the expenditure needed to hold Afghanistan, this isn’t a calculation they would ever make for their home turf.

Finally, even in the extremely unlikely event there was a successful revolution in a Western state, the rest of the West would step in to make sure the existing regime was preserved. Western leaders aren’t going to tolerate the example of one of their own liberal democratic regimes being overthrown. Even if a revolutionary state survived an outside military intervention, they would be so isolated diplomatically and economically, with so much effort from the outside to empower liberal forces, that the new regime would quickly face ruin.

The resiliency of democracy

No revolution from below, but could we expect a bifurcation of elites, like what happened in America before the Civil War, or France before its revolution? Peter Turchin has been drawing attention to the fact that the United States is in a time of elite overproduction for years now, which makes a social collapse far more likely.

Still, it’s hard to envision under this system. Modern capitalism is very successful at maintaining at least the belief in fluid social mobility in a way no other system could. There isn’t any great divergence between the interests of any of the major segments of the economic elites.

The closest thing to this is the shift of Silicon Valley billionaires like Peter Thiel, Elon Musk and David Sacks to supporting “anti-woke”, anti-DEI politics, going so far as to throw their support behind Donald Trump. Their demand is still for a mere course correction of the current system. Thiel, for example, wants the US to be more meritocratic and less sidetracked by wokeism so it can more successfully assert its dominance over a rising China. Not very revolutionary, and the cost of losing is not so great for these men that it would be worth risking it all to try and take down a system their whole fortune is tied to.

The clear pattern that emerges in studying the revolutions of modern history is that they were typically led by a bourgeois economic class against an old aristocracy or monarchy. Often, they were new nations striking out and demanding independence from a declining empire. In either case, the demand was for more democracy, more sovereignty. These are the kinds of demands that are easy to organise millions of people around: “replace the tyrant and give power to the people”, “replace the foreign occupier and give power to the nation”; a far cry from the often niche grievances collapsitarians fixate on.

Once mass democracies are established, the path to political disintegration is much more obstructed. Part of the reason for this is that it’s so hard to challenge the legitimacy of mass-democracy once a population has accepted its assumptions about the world. A lot of people might hate the current establishment, but how many reject the legitimacy of the elections, universal suffrage, liberal rule of law, and “democratic values” from which they draw their leigitimacy?

The closest we got to that was in 2020, when, after Biden’s election, over 70% of Republicans, and one third of Americans, believed his election was illegitimate. It’s really hard to imagine a scenario more ripe for serious civil conflict than one side thinking the other overturned democracy and rigged an election, ousting a populist figure with a cult following.

And what happened? America didn’t even come close to a civil war. The Stop The Steal movement held some protests demanding change, which culminated in January 6th, where a lot of angry Trump supporters stormed Congress, walked around a bit, then left. The only thing that resulted from that was those people being rounded up and jailed, including the leadership of militia groups such as the Oath Keepers, whose founder was jailed for 18 years.

Four years later, most Republicans still believed the 2020 election was illegitimate, but they went to the polls in 2024 with even more enthusiasm anyway.

People in Western societies are just too comfortable to bother with something as messy as revolution, even if they believe their government to be illegitimate. Collapsitarians make grand promises about an inevitable economic crisis bringing about an inevitable revolution, as if even the worst recession today would be comparable to the kind of immiseration that preceded revolutions in the past. Other revolutions were preceded by extreme economic immiseration, often including actual starvation. In 1788, there was a famine in France which starving Frenchmen blamed on a conspiracy by the elites. The fact is, most of us can’t imagine experiencing the kind of desperation that drove people to revolution, and with the comforts offered by the modern welfare state, we probably never will.

Back to Turchin, his model had predicted social unrest in America peaking in the early 2020s, but this doesn’t necessitate a civil war. The periods of the early 1970s and late 1920s were also times of intense unrest, but each was followed by long periods of stability without passing through a civil conflict.

With today’s dynamics of social media, decline of traditional sources of authority, and extreme polarisation, it’s hard to see things ever returning to the kind of consensus politics we experienced just a decade ago, but there may be an exhaustion with how resilient the system has been and increased cynicism about populist movements. After his return to power, Trump is now set to fade out of the center stage of politics after his presidency, and his potential successors are much less polarising.

I believe diversity and ongoing mass-immigration into Western countries will continue to drive unrest and polarisation, but opponents of this agenda should not put their faith in some future uprising or collapse to reverse it. Change will be slower, and will require a lot of hard work winning hearts and minds, organising, gaining power, and taking advantage of disrupting events.

It’s tempting to cling to the fantasy of an inevitable revolution, as it offers an escape from the arduous and often thankless work of building a political movement. Most collapse fantasists are individualists, and they don’t want to accept that a political project to preserve their heritage requires real sacrifice from them — sacrifices which they may never see the fruits of in their lifetime.

The lesson of this article is there is no short cut: the system is more resilient and has more to offer people than its opponents care to admit. Our enemies are working tirelessly to decide the future, it’s time to get to work.

1. Goldstone, Jack A. Revolutions: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press, 2014.

2. Himmelstein, Jerome L., and Michael S. Kimmel. Review of States and Revolutions: The Implications and Limits of Skocpol’s Structural Model, by Theda Skocpol. American Journal of Sociology 86, no. 5 (1981): 1145–54.

This article originally appeared on Keith Woods’ Substack and is republished by The Noticer with permission.

It is from his book Nationalism: The Politics of Identity, available on Amazon. If you enjoy his writings, please consider purchasing it and leaving a positive review.