Australia is being bled financially dry as billions of dollars are sent offshore each year in remittances, and India and China are the largest recipients.

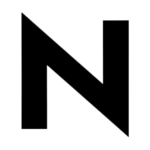

The amount of money that exits the country has exploded over the last few decades. Annual remittance payments were only around US$300 million – or 0.2% of GDP – in 1980, and they remained well under US$1 billion dollars until the turn of the century.

Since then, these figures have skyrocketed. Annual remittance outflows increased to US$5 billion by 2010, then to US$7 billion by 2020. They are now over US$10.3 billion (AU$16.63 billion) – or 0.6% of GDP – per annum.

The top five recipients are India, China, Philippines, Vietnam and the UK, and in 2019 almost half the money that left Australia flowed to these five nations alone, and since 2022 Australia has seen a record increase in Indian, Chinese and Filipino immigrants.

Australia also has a huge net deficit in remittance payments, with the amount of money sent abroad far exceeding what we receive. According to the Migration Policy Institute, annual remittance inflows were only worth US$1.6 billion, resulting in a net outflow of US$8.6 billion, up from just US$351 million in the year 2000.

Australia maintains enormous imbalances in remittances with almost every country of the world. Remittances to China, for example, were over $3 billion in 2021 yet we received $6 million in return. Remittances to Thailand were around $680 million yet we received just $2 million back.

There are many countries from which Australia receives zero in remittances. Remittances out of Australia to Lebanon, Nepal, Kenya and Bangladesh were over US$719, $466, $198, and $191 million in 2021, yet we didn’t see a cent from any of these countries in return.

New Zealand, Singapore and Canada are among a handful of nations in which we maintain a positive balance in remittances.

The surge in money exiting Australia has been driven by international students. As economist Leith Van Onselen has shown, this explosion in outbound remittances has coincided with an explosion in foreign students.

As student visa numbers grew from 350,000 to 650,000 between 2021 and 2023 so too did remittances, with outflows increasing from US$3 billion to US$8 billion during that time.

Much of the recent growth in remittances is due to an influx of Indian immigrants. The number of Indian-born people in Australia has doubled over the last decade to close to 1 million people, making them one of the largest and fastest growing immigrant groups .

This has happened at the same time as India has become the largest recipient of our remittance payments. India received US$3.9 billion in remittances from Australia in 2021, making it by far the biggest beneficiary of our remittance payments. Australia, in contrast, received US$5 million from India in return.

And this was before record numbers of arrivals from India since Labor came to government in May 2022.

India is by far the world’s largest receiver of remittances, and according to the World Bank, it received US$129 billion – or 3.3% of its GDP – in remittances in 2023. This is more than double second-placed Mexico, at $61 billion, or third-placed Philippines with $38 billion.

Among the top ten sources of remittances to India are the UAE, the United States, Canada and Australia.

Many countries now depend on remittances for a substantial amount of their income, and nations like Nepal, El Salvador and Samoa now see a fifth to a third of their overall GDP stemming from remittance payments.

Many in the developing world rely on remittances too, and they are a key reason why immigrants flock to countries like Australia.

A 2023 report by 3Gem for Western Union found that “over half (51%) of migrants living in Australia believe their friends or family would be in poverty if it wasn’t for them sending regular payments back home and that 57% state that members of their family would not be able to afford medical treatment”.

The survey of 1,500 immigrants also found that 92% had sent money home in the past 12 months, 67% said being able to do so was a “key factor in their decision to move to Australia”, and that an average of 11% of migrants’ annual incomes were sent back to their home countries in remittance payments.

Header image credit: Left, Google Street View. Right, Migration Policy Institute